|

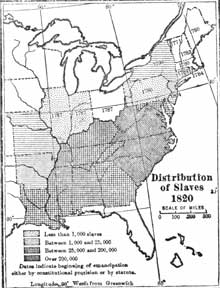

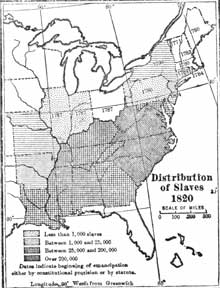

1820 Missouri Compromise

|

|

|

| This was the first major compromise between those states favoring slavery and those opposing slavery. Under the terms of the agreement, Missouri was to be admitted as a slave state, while Maine was admitted as a free state. The rest of the territory acquired from France north of the latitude 36'30' would be free states, while south of that point would be slave states. |

|

Background

The fight over whether or not to continue slavery in the United States was a major issue from the very early days of the Republic. In 1774, Benjamin Franklin, was one of the founding members of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery. Franklin described slavery as "an atrocious debasement of human nature" at the Continental Congress. At the First Continental Congress it was agreed to discontinue the slave trade. Continuation

|

|

|

|

Tallmadge Amendment

By 1819, the population of Missouri had grown to the point where it was ready for statehood. Ten thousand slaves already lived in Missouri and it was assumed Missouri would become a slave state. On February 13th James Tallmadge, a congressman from Poughkeepsie, New York, introduced a resolution in Congress making two modifications to the Missouri Enabling Act (The Enabling Act would give Missouri statehood). This act would ban any further importation of slaves into Missouri and would set in motion the gradual emancipation of the slaves currently residing in Missouri. Thus, a one term Congressman began a battle over slavery that was only ended by the Civil War.Continuation |

|

|

The Effect

The Missouri Compromise (1819) set a number of precedents. First, states would enter the Union in pairs, slave states and free states. This compromise helped the Southern states, as they were often admitted to the Union sooner than they would normally have been admitted. Second, the Missouri Compromise delayed the sectional breakup of the Jefferson's Republican party. The battle over Missouri signified a solidification of the Southern opposition to the eventual emancipation of the slaves. Until the fight over Missouri's admission to the Union, there was some hope the South would follow the path indicated by many of the founders; a path leading to the eventual voluntary emancipation of all slaves. By the time the Missouri Compromise was reached, it was clear this was not meant to be. The road to the eventual Civil War was laid. Of course, until the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, the restriction on slave states North 36º30º line held strong.Continuation

|

|

|

|

Both Thomas Jefferson and John Quincy Adams wrote about the compromise from very different perspectives.

|

|

Jefferson wrote: This momentous question, like a fire bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror, I considered it at once the knell of the Union. It is hushed indeed, for the moment. But this is a reprieve only, not a final sentence. I regret that I am now to die in the belief that the useless sacrifice of themselves by the generation of 1776, to acquire self-government and happiness to their country, is to be thrown away by the unwise and unworthy passions of their sons, and that my only consolation is to be, that I live not to weep over it. |

|

|

John Quincy Adams charged: If slavery be the destined sword of the hand of the destroying angel which severs the ties of this Union, the same sword will cut in sunder the bonds of slavery itself. A dissolution of the Union for the cause of slavery would be followed by a servile war in the slave-holding States, combined with a war between the two severed portions of the Union. It seems to me that that its result might be the extirpation of slave from this whole continent and, calamitous and desolating as this course of events in its progress must be, so glorious would be the final issue that as God should judge me, I dare say this it is not to be desired.

|

|

|

>

>