The Fight In Congress Over Missouri

With the population of Missouri growing it was clear that Missouri would soon join the Union. The question of whether it would be a slave or free state weighed on the American political scene. Congressman James Tallmadge of New York introduced a bill in Congress that would ban the importation of slaves into Missouri

With the population of Missouri growing it was clear that Missouri would soon join the Union. The question of whether it would be a slave or free state weighed on the American political scene. Congressman James Tallmadge of New York introduced a bill in Congress that would ban the importation of slaves into Missouri

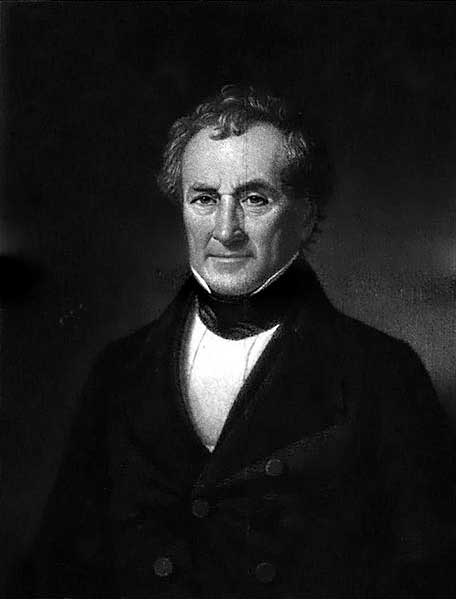

By 1819, the population of Missouri had grown to the point where it was ready for statehood. Ten thousand slaves already lived in Missouri, and it was assumed Missouri would become a slave state. On February 13th, James Tallmadge, a congressman from Poughkeepsie, New York, introduced a resolution in Congress proposing two modifications to the Missouri Enabling Act (which would grant Missouri statehood). This act would ban any further importation of slaves into Missouri and set in motion the gradual emancipation of the slaves currently residing in Missouri. Thus, a one-term congressman began a battle over slavery that was only ended by the Civil War.

Following the introduction of the amendment, a very heated debate broke out in Congress. Opponents of the amendment threatened that if it were passed, the Union would fall apart. Northern congressmen lined up in support of the Tallmadge Amendment, stating: "If we reject the amendment and suffer this evil, now easily eradicated, to strike its roots so deep in the soil that it can never be removed, shall we not furnish some apology for doubting our sincerity when we deplore its existence? Shall we not expose ourselves to the same kind of censure which was pronounced by the Savior of Mankind upon the Scribes and Pharisees, who built the tombs of the prophets and garnished the sepulchers of the righteous, and said, if they had lived in the days of their fathers, they would not have been partakers with them in the blood of the prophets, while they manifested a spirit which clearly proved them the legitimate descendants of those who killed the prophets, and filled up the measure of their fathers' iniquity."

The Southern congressmen banded together to unanimously oppose the amendment. While defending slavery, they also presented the question as one of simple states' rights. John Scott, a delegate from Missouri, said: "Can any gentleman contend that laboring under the proposed restrictions, the citizens of Missouri would have the rights, advantages, and immunities of other citizens of the Union?"

The House passed the Tallmadge Amendment to restrict slavery in Missouri. However, the Senate rejected the amendment. When the House refused to pass the Missouri Enabling Act without the amendment, there was no choice but to put off the decision on what to do with Missouri until the next Congress. With Congress recessed, the fight went to the people. In the North, despite the ongoing economic panic, supporters of the Tallmadge Amendment organized anti-slavery rallies. The Republicans redoubled their efforts to get Missouri admitted without conditions during the Congressional recess.

Behind the scenes, however, President Monroe, Henry Clay, and others worked towards finding a compromise. For a number of years, the "District of Maine," which was part of the State of Massachusetts, had requested to become a separate state. In June 1819, the legislature of Massachusetts agreed to the request. The Senate combined the admission of Missouri and the admission of Maine into one bill, connecting the admission of Maine to the admission of Missouri. This alone was not enough to get Missouri admitted to the Union. Senator Jesse Thomas of Illinois, who had voted for the Tallmadge Amendment, made the proposal that carried the day. Senator Thomas suggested Missouri be admitted as a slave state, but that all states north of the 36º 30' latitude (the northern border of Missouri) be admitted as free states. With this proviso, despite the continued opposition of most of the Northern Congressional delegation, enough northerners were willing to vote for Missouri's admission to the Union. As a result, in 1819 Missouri was admitted into the Union.

>

>