Cuban Missile Crisis 1962

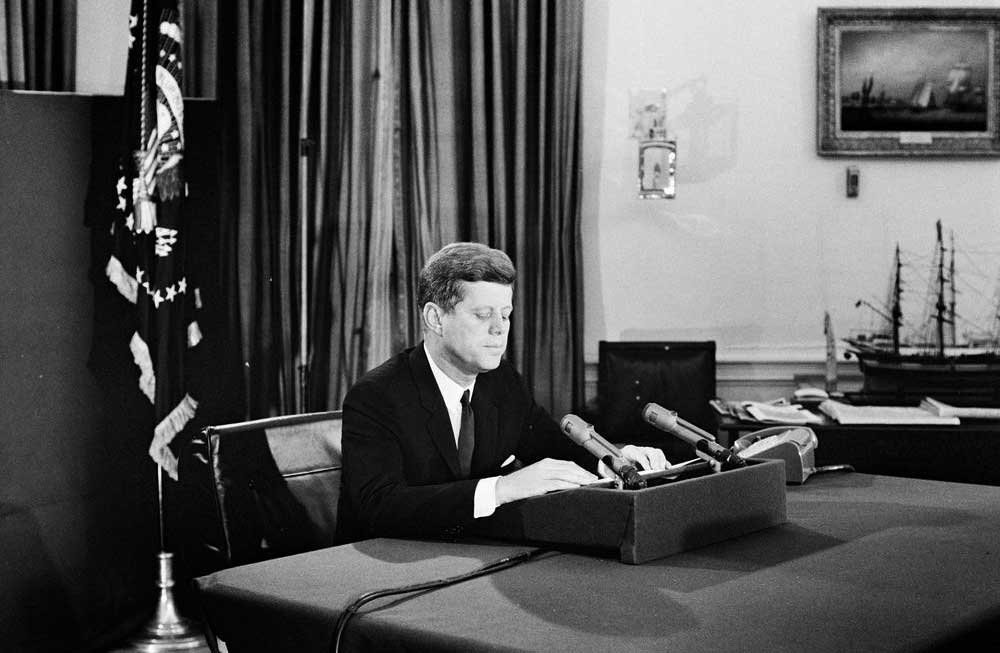

JFK Addressing the Naiton

The Soviet Union secretly placed nuclear-armed missiles in Cuba, thus upsetting the balance of power. American reconnaissance aircraft discovered the missiles in October, before they could become operational. President Kennedy demanded their removal and instituted a blockade of Cuba, while calling up reserve forces. The world stood on the brink of a nuclear holocaust, but the Soviets, under Premier Khrushchev, blinked and agreed to remove their missiles.

n the aftermath of the Bay of Pigs crisis, the United States continued to make plans for the ouster of Fidel Castro. At the same time, the Soviet Union stepped up its aid to Cuba. In August 1962, reports reached Washington of a significant increase in Soviet aid. Reports stated that over the previous month, 20 Soviet ships had arrived in Cuba with military supplies. The buildup was unprecedented.

Reconnaissance photos soon made it apparent that the Soviets were installing Sam 2 anti-aircraft missiles in Cuba. The Sam 2 was good only against very high flying aircraft such as a U-2. Thus, the reason for the missile buildup became the subject of much speculation. If the missiles were not there to protect against an invasion, they were obviously there to protect something else. Many theories abounded throughout September and early October, but there was no hard evidence.

On October 14th, the sky over Cuba was clear, and a U-2 flight took place. By the following night, photo experts had concluded that the Soviets were building medium-range missile sites in Cuba. At 8:45 AM on Tuesday, Oct. 16th, national security advisor McGeorge Bundy knocked on the president's door and broke the news to him. Kennedy immediately asked that a meeting be set up with key advisors. They were Vice President Lyndon Johnson; Secretary of State Dean Rusk; Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara; Attorney-General Robert Kennedy; Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Maxwell D. Taylor; C.I.A. Director John McCone; Secretary of the Treasury C. Douglas Dillon; U.N. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson; Undersecretary of State for economic affairs George Ball and advisors McGeorge Bundy, Ted Sorensen, Roswell Gilpatric, Llewellyn Thompson, Alexis Johnson and Edwin Martin. This group became known as the Excom. In addition, former Secretary of State Dean Acheson and Wall Street banker Robert Lovett attended some of the meetings.

For almost a week, the president and his advisor tried to decide on a course of action. In the midst of the meetings, on Thursday, Soviet foreign minister Gromyko had a meeting with Kennedy. At the meeting, he gave assurance that the Soviets would never place any offensive weapons in Cuba. The initial response, among most of the participants, was that the missiles had to be bombed. Slowly a consensus developed on an alternative track, "a blockade against Cuba." There were a number of reasons for the shift. First, a surprise attack on the missiles reminded many of Pearl Harbor in reverse. Second, it soon became clear that there was no such thing as a surgical air strike to remove the missiles. It would take almost 1,000 sorties to accomplish 90% of the mission. Finally, Kennedy and his advisors felt that foreign governments would not understand the need for such drastic actions. Thus, the decision was made to blockade, or "quarantine" Cuba. On Monday, October 22, Congressional leaders were brought to the White House and informed of the crisis.

That evening at 8:00 PM, the president addressed the country about the crisis. As he spoke, 22 US airforce planes turned toward Cuba, in case the country responded to Kennedy's speech with an attack. In his speech, he announced the quarantine, demanded that the missiles be removed, and stated that further actions would be taken if they remained in place.

Immediately, 56 American warships steamed to their positions to enforce the blockade. All military leaves were canceled, and US forces were placed on a DEFCON-3 alert. Plans went ahead, and troops began amassing for an attack on Cuba.

The Organization of American States met and voted unanimously to condemn the Soviet actions, and demand the removal of Soviet missiles. The world stood still. It seemed that nuclear war was a very real possibility.

On Wednesday, as the blockade went into effect, the White House received word that a number of Russian ships had stopped in mid-sea. Rusk said to Bundy: "We're eyeball to eyeball, and I think the other fellow just blinked." Nevertheless, time was passing. Air strikes were scheduled for the morning of October 30th. A series of messages passed back and forth between Kennedy and Khrushchev. Some were more belligerent, others less so. It looked like an agreement could be reached, but no one was quite sure. Finally, on the morning of October 28th, Moscow radio announced that there would be an important message that evening, Moscow time. At 9:00 AM, the text of a letter from Premier Khrushchev to President Kennedy was read on the air: "In order to complete with greater speed the liquidation of the conflict dangerous to the cause of peace, to give confidence to all people longing for peace, and to calm the American people who, I am certain, want peace as much as the people of the Soviet Union, the Soviet Government, in addition to previously issued instructions on the cessation of further work at building sites for the weapons, has issued a new order on the dismantling of the weapons which you describe as "offensive," and their crating and return to the Soviet Union."

The crisis was over - the Soviets had backed down. They really had had no choice. Later information was to show that the Soviets only had 20 inaccurate Ballistic missiles and 155 heavy bombers pointed towards the United States, while the United States had 156 intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), 144 Polaris missiles, and 1,300 bombers ready to strike.

>

>