The person who is considered the father of the locomotive is George Stephenson. He was a self educated man who could hardly read. His first locomotive was called the Bluecher.

George Stephenson, widely regarded as the “father of the locomotive,” was a self-taught engineer whose innovations changed transportation forever. Born in 1781 in Wylam, England, to a poor family, Stephenson had limited educational opportunities. Despite this, he possessed a keen interest in mechanics and engineering from a young age. In his early years, he worked in coal mines, performing various manual labor tasks. Over time, he managed to save enough money to learn the basics of reading, writing, and arithmetic, teaching himself largely without formal instruction. Stephenson’s determination to learn set the stage for his groundbreaking contributions to steam-powered locomotion.

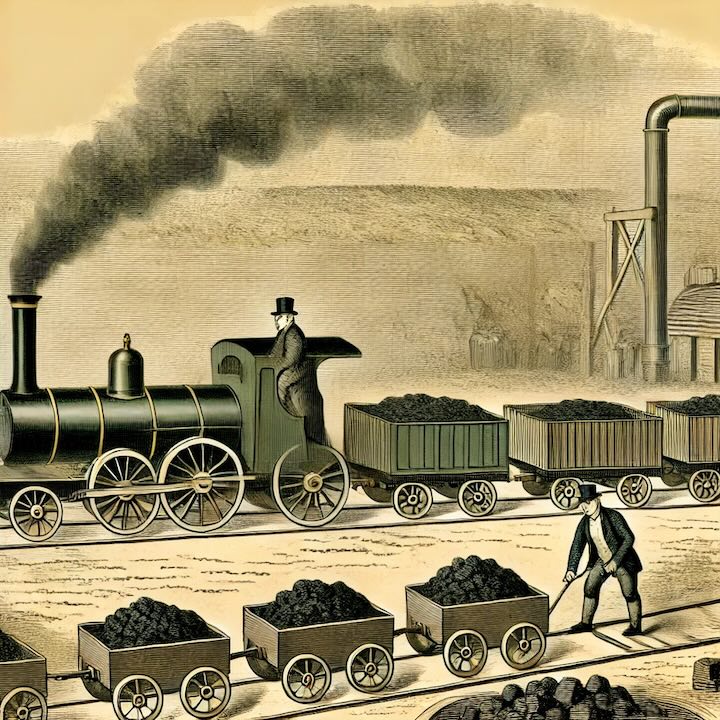

Stephenson’s career in engineering began as a brakeman and engine man, where he developed a deep understanding of machinery. His early experiences with steam engines, used to pump water from coal mines, gave him hands-on expertise in managing and repairing steam-powered systems. The turning point in his career came when he built his first locomotive, the Blücher, named after the Prussian General Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, who fought alongside the British at Waterloo. Constructed in 1814, the Blücher was designed specifically for hauling coal wagons at the Killingworth Colliery in northeast England. Stephenson’s locomotive stood out for its ability to pull a heavy load at a higher speed than horse-drawn systems, which were commonly used at the time.

What set the Blücher apart was Stephenson’s innovative design, which included flanged wheels to keep the locomotive securely on its tracks, a crucial advancement for stability and efficiency. This innovation marked a significant improvement over previous locomotive attempts, which often suffered from derailment or lack of traction. Although rudimentary by modern standards, the Blücher could pull several loaded coal wagons over a short distance, showcasing the feasibility of steam power for industrial transport. The success of the Blücher established Stephenson as a leading figure in locomotive development and proved that steam locomotives could revolutionize transportation.

Following the success of the Blücher, Stephenson continued to refine his designs, leading to the creation of the Locomotion No. 1, which pulled the first passenger train on the Stockton and Darlington Railway in 1825. This milestone marked the beginning of the railway age, as the Stockton and Darlington Railway was the world’s first public railway to offer both freight and passenger services powered by steam. Stephenson’s improvements in boiler design, the use of a multi-tubular boiler to increase efficiency, and his development of a blast pipe for better exhaust management set new engineering standards and were incorporated into future locomotives worldwide.

Perhaps Stephenson’s most famous locomotive, the Rocket, was built in 1829 with his son, Robert. The Rocket won the Rainhill Trials, a competition designed to determine the best locomotive for the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, one of the first inter-city railways. The Rocket’s success helped establish the standard for future steam locomotives, as it incorporated several design features that would become the norm, including the blast pipe and separate firebox.

Beyond his engineering accomplishments, Stephenson’s dedication to safety and standardization had lasting impacts. He advocated for uniform rail gauge width, a recommendation that eventually led to the adoption of the “Stephenson gauge” (4 feet, 8.5 inches), still in use today.

In summary, George Stephenson’s contributions to locomotive engineering laid the foundation for modern railways. His self-education, hands-on expertise, and relentless innovation propelled steam locomotion forward, and his legacy endures in the continued use of the technologies he pioneered. Stephenson’s work not only transformed transportation but also laid the groundwork for the global spread of railways, fueling industrial growth and expanding human mobility in unprecedented ways.

>

>