Edmund Cartwright invented the power loom in 1784. The power loom was a method to automate the final stage of textile production the weaving. It was a complicated machine that had to a set of sequential steps in order to do the weaving. The Power Loom allowed the weaving to keep up with the newly accelerated spinning of thread.

Edmund Cartwright, an English inventor, revolutionized the textile industry by inventing the power loom in 1784. His power loom was an innovative machine designed to automate the process of weaving, the final and critical stage of textile production. Prior to Cartwright’s invention, weaving was done manually on traditional handlooms, which was a labor-intensive and time-consuming process. The power loom was intended to address this inefficiency by mechanizing the weaving process, making it much faster and less reliant on human labor.

Cartwright’s invention came at a crucial moment in the development of the textile industry. By the late 18th century, advancements in other stages of textile production, such as the invention of the spinning jenny by James Hargreaves and Richard Arkwright’s water frame, had greatly accelerated the process of spinning thread. These innovations created an abundance of thread, but the traditional handlooms used for weaving were not able to keep up with the increased production of spun fibers. There was a significant bottleneck in the textile production process, as spinning and weaving were not aligned in terms of productivity. Cartwright recognized this gap and sought a solution that would allow weaving to match the pace of spinning, thereby transforming the textile industry and meeting the growing demand for fabric.

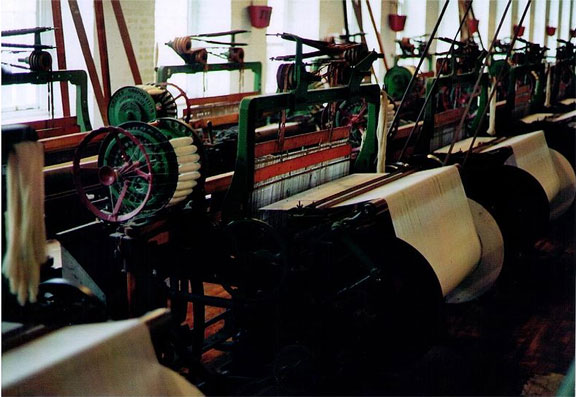

The power loom was a complex machine requiring a precise series of steps to weave fabric effectively. It was equipped with a mechanized system that performed the actions previously done manually by weavers: the raising and lowering of warp threads, the passing of the weft thread through the warp, and the tightening of the threads to create a strong, uniform fabric. By mechanizing these steps, the power loom increased both the speed and accuracy of the weaving process, producing fabric at a rate much faster than traditional methods.

Cartwright’s original power loom design went through several improvements. Initially, his prototype faced significant challenges and skepticism, as it was prone to mechanical issues and was costly to operate. Nevertheless, Cartwright’s idea proved sound, and subsequent refinements by others eventually made the power loom more efficient and reliable. By the early 19th century, power looms had become an integral part of textile factories in England, contributing to the growth of the Industrial Revolution. In these factories, the power looms were powered by steam engines, further enhancing their efficiency and making them capable of producing fabric on a mass scale. This shift marked a new era in the textile industry, as production could now meet the demands of a rapidly growing population and emerging consumer culture.

The power loom had far-reaching economic and social implications. It significantly reduced the need for skilled hand weavers, leading to widespread job displacement and labor unrest, especially in regions where traditional weaving was a primary occupation. Many weavers, whose livelihoods depended on manual weaving, protested against the new machinery. This period saw the rise of the Luddite movement, where groups of workers destroyed machinery that they believed threatened their jobs. Despite this resistance, the power loom continued to spread, as the benefits of mass production became undeniable.

Cartwright’s power loom transformed textile production and paved the way for the modern factory system. It allowed for fabrics to be produced in greater quantities, at lower costs, and with consistent quality. By automating weaving, Cartwright not only solved a production bottleneck but also laid the groundwork for future innovations in industrial manufacturing, shaping the development of mechanized industries around the world. The power loom stands as a symbol of the Industrial Revolution, representing both the promise of technological progress and the social upheaval it can bring.

>

>