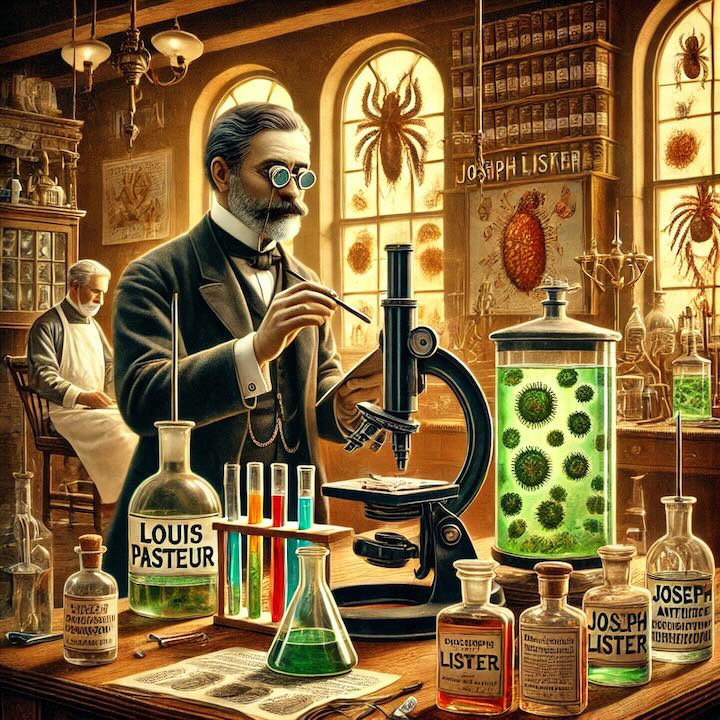

1861 Pasteurization Begun

In 1861, thanks to Louis Pastuers work on microorganisms, pasteurization was introduced to milk, beer and other foods to preserve them.

In 1861, Louis Pasteur’s groundbreaking work on microorganisms laid the foundation for pasteurization, a process that would revolutionize the preservation of milk, beer, and other perishable foods. Before Pasteur’s discoveries, food spoilage was a common and poorly understood phenomenon, leading to health risks and economic losses. Pasteur, a French chemist and microbiologist, embarked on a series of experiments to investigate why certain foods and drinks went bad and posed risks to consumers. His research revealed that spoilage and fermentation were caused by microscopic organisms, such as bacteria and yeast, which thrive under specific conditions. Pasteur’s experiments demonstrated that heating liquids to a certain temperature could kill these harmful microbes, thus preventing spoilage and extending shelf life. This process became known as “pasteurization” in honor of his pioneering work.

Pasteur initially applied his findings to the wine and beer industries, which faced significant problems with contamination and spoilage. At the time, these beverages were essential not only for consumption but also for commerce, and spoilage resulted in substantial economic losses. By heating the wine and beer to a controlled temperature, Pasteur found that he could effectively eliminate the microorganisms responsible for spoilage without compromising the taste and quality of the products. This discovery had immediate implications for the beverage industry, allowing for more consistent production, storage, and distribution of alcoholic beverages.

The application of pasteurization to milk, however, was one of the most impactful uses of Pasteur’s technique. During the 19th century, milk-borne diseases, such as tuberculosis, brucellosis, and typhoid fever, were widespread and posed a severe public health concern. Contaminated milk, often a result of poor hygiene practices in dairy farms, became a leading cause of illness and death, especially among children. Recognizing the potential benefits of pasteurization for milk safety, health officials and scientists began advocating for its use in the dairy industry. Heating milk to a temperature of around 63°C (145°F) for 30 minutes or 72°C (161°F) for 15 seconds—known as low-temperature, long-time (LTLT) pasteurization and high-temperature, short-time (HTST) pasteurization, respectively—became standardized methods to eliminate pathogens.

The adoption of pasteurization transformed public health, significantly reducing milk-borne illnesses and changing the way society viewed food safety. As pasteurization gained acceptance, milk became a safer and more reliable source of nutrition. This was particularly crucial in urban areas, where fresh milk was often difficult to procure and store safely. The process also paved the way for improvements in dairy hygiene standards, encouraging practices that would further protect consumers from foodborne diseases. Pasteurization’s success extended to other perishable foods, including juices, canned goods, and certain processed foods, which benefited from reduced microbial contamination and longer shelf lives.

Pasteur’s work not only improved food safety but also underscored the importance of microbiology in public health. His research inspired future scientists to explore new ways to combat infectious diseases and develop safer food preservation methods. Today, pasteurization remains a cornerstone of food safety protocols worldwide, a testament to Louis Pasteur’s enduring legacy and his transformative impact on science and public health. Through his work, Pasteur demonstrated that understanding and controlling microorganisms could prevent disease, save lives, and secure the food supply, a legacy that continues to benefit societies across the globe.

>

>