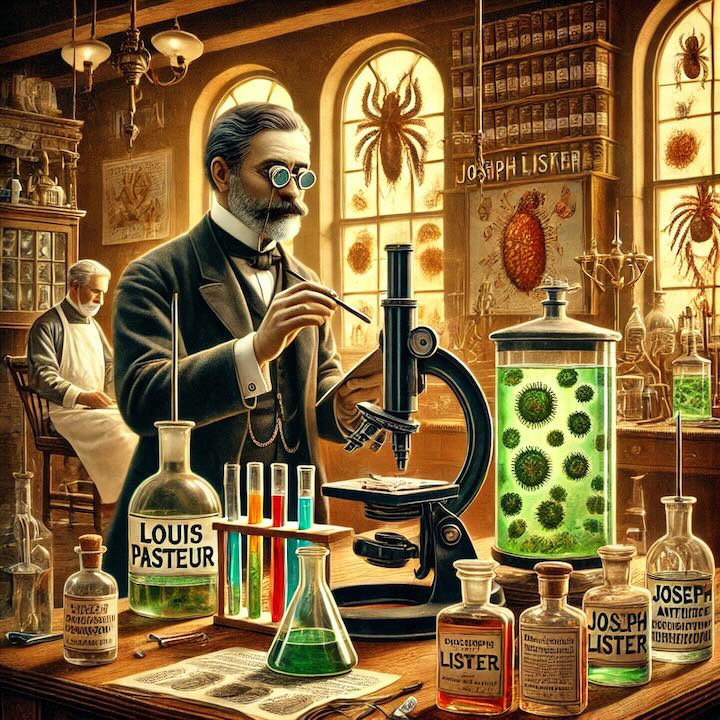

1877 Germ Theory of Disease

Louis Pasteur investigated microorganisms. This resulted in his presentation of the Germ Theory of disease. Joseph Lister went on to initiate the practice of insuring that surgeons were clean before they conducted surgery.

In 1877, Louis Pasteur, a pioneering French scientist, made groundbreaking advancements in the study of microorganisms, which led him to present the Germ Theory of disease. This theory proposed that microorganisms, or “germs,” were the cause of various diseases and infections, a concept that challenged centuries of traditional medical beliefs. Before Pasteur’s work, most people believed in the “miasma theory,” which held that diseases were spread by “bad air” or poisonous vapors. Pasteur’s research, however, suggested a revolutionary new idea: that tiny, invisible organisms were responsible for causing illness. This discovery was a turning point in both medical and scientific history and had an immediate impact on the fields of medicine, hygiene, and public health.

Pasteur’s investigations into fermentation and spoilage initially led him to this theory. By studying how certain microorganisms caused wine, beer, and milk to spoil, he realized that these organisms were capable of influencing not only food but potentially the human body as well. In his experiments, he demonstrated how bacteria and other microorganisms were not spontaneously generated, as was widely believed, but rather introduced from external sources. This insight laid the foundation for understanding infectious diseases and the transmission of pathogens.

Building on Pasteur’s Germ Theory, Joseph Lister, a British surgeon, implemented practical applications of these findings in medical settings. Lister realized that if microorganisms were responsible for disease, then the surgical environment needed to be as sterile as possible to prevent infections. At that time, surgery was a perilous endeavor with high rates of infection and mortality. Surgical instruments were often reused without proper cleaning, and surgeons did not take precautions to maintain cleanliness. Recognizing the implications of Pasteur’s discoveries, Lister introduced antiseptic practices, particularly using carbolic acid (phenol) to sterilize surgical tools, wounds, and the hands of medical personnel.

Lister’s innovations transformed the field of surgery. He instructed his medical team to wash their hands thoroughly before procedures, to sterilize instruments, and to ensure that the surgical environment was clean. These practices, though initially met with skepticism, proved highly effective in reducing infection rates. His antiseptic methods drastically lowered post-surgical mortality rates and demonstrated the importance of cleanliness in preventing the spread of infections. Lister’s work not only improved patient outcomes but also changed the culture of surgery, making sterile environments and antiseptic techniques standard in medical practice.

The Germ Theory and antiseptic practices revolutionized the medical field by establishing a scientific basis for disease prevention. Pasteur and Lister’s combined contributions marked the beginning of modern bacteriology and laid the groundwork for advancements in immunology, virology, and epidemiology. With a better understanding of microorganisms, scientists could now develop vaccines, a path Pasteur would later explore with his development of vaccines for rabies and anthrax.

The long-term impacts of Germ Theory extended beyond medicine. This new understanding of disease transmission influenced public health policies, sanitation practices, and even urban planning. Governments began to invest in clean water supplies, waste management, and public sanitation systems to prevent outbreaks of infectious diseases. Pasteur’s and Lister’s discoveries led to new standards of hygiene, shifting societal views on cleanliness and health. They encouraged a shift from treating symptoms to preventing disease, which continues to be a central tenet in healthcare today.

Through their work, Louis Pasteur and Joseph Lister reshaped our understanding of health, transforming medicine into a science grounded in empirical research and hygiene. Their legacy endures in the sterile practices and infection control protocols that remain foundational in modern medical facilities worldwide.

>

>