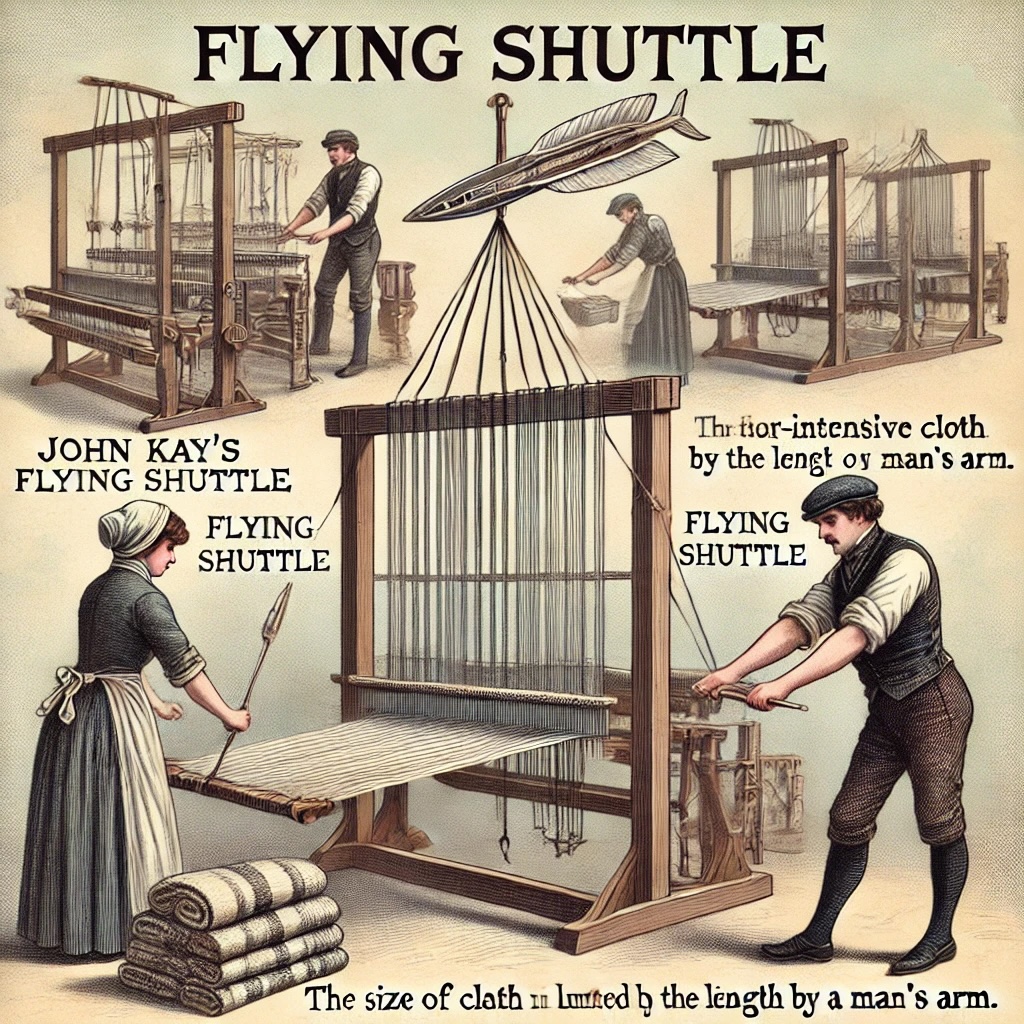

In 1733 John Kay invented the Flying Shuttle. The shuttle allowed wool to be produced much more efficiently. Before the Flying Shuttle wool could only be produced to the width of a mans arm.

John Kay, born in 1704 in Bury, Lancashire, was the son of a wool manufacturer, and he grew up surrounded by the textile industry. Kay’s father, Robert, owned a small wool production business, and John was involved in the family business from an early age, learning the ins and outs of textile production. While managing one of his father’s plants, John Kay began to observe inefficiencies in the weaving process, which at the time required significant manual labor. In particular, he saw an opportunity to improve the operation of the loom, a machine used to interlace yarn and thread to create cloth. His keen insight and innovative mind would eventually lead him to one of the most significant advancements in the textile industry—the Flying Shuttle.

In 1733, John Kay patented what was officially described as a “New Engine Machine for Opening and Dressing Wool,” a mechanism that became widely known as the Flying Shuttle. Before his invention, the weaving process was labor-intensive and slow. Weavers had to manually pass the shuttle (a tool used to weave the yarn through the threads) through the loom, which was not only time-consuming but also physically limiting. The size of the cloth produced was constrained by the weaver’s reach, as the shuttle could only be passed back and forth as far as the arms could stretch. This method required two workers for wide fabrics—one on each side of the loom.

Kay’s Flying Shuttle was revolutionary because it allowed a single weaver to operate a loom by themselves, regardless of the cloth’s width. The shuttle, mounted on wheels and running along a track, could be propelled across the loom with a simple tug of a cord. This drastically increased the efficiency of weaving, doubling a weaver’s output while simultaneously increasing the potential width of the fabric that could be produced. The innovation was particularly impactful in the production of broadcloth and other large textiles, which had previously required multiple workers.

While Kay’s invention was a breakthrough for textile manufacturing, it had unintended consequences for the workers. The introduction of the Flying Shuttle threatened the jobs of many weavers, as manufacturers no longer needed two workers for each loom. In response, many weavers strongly opposed Kay’s invention. They feared that widespread adoption of the Flying Shuttle would lead to unemployment and lower wages. Their resistance was not just vocal; in some cases, it became violent. Kay’s house was attacked by angry mobs, and he faced significant hostility from those who believed the new technology would render their skills obsolete.

Although the manufacturers quickly saw the economic benefits of the Flying Shuttle and adopted it widely, they were reluctant to pay Kay the royalties he was owed under his patent. Despite the fact that his invention transformed the textile industry, Kay found himself embroiled in lengthy and costly legal battles to defend his rights. The refusal of many manufacturers to honor his patent claims forced Kay into financial ruin. He spent much of his life fighting for the recognition and compensation he deserved but was ultimately unsuccessful. In 1779, John Kay died impoverished in France, having never reaped the rewards of his revolutionary invention.

Kay’s Flying Shuttle was a pivotal development in the early stages of the Industrial Revolution. It marked the beginning of a series of innovations that would transform textile production from a manual craft to a mechanized industry. Though he did not live to see the full impact of his invention, Kay’s work laid the groundwork for the mechanized looms that would follow, significantly increasing the speed and scale of cloth production. Today, he is remembered as a key figure in the history of textile manufacturing, and his Flying Shuttle remains one of the most important technological advancements of the 18th century.

>

>