1903 -Panama Independent From Columbia

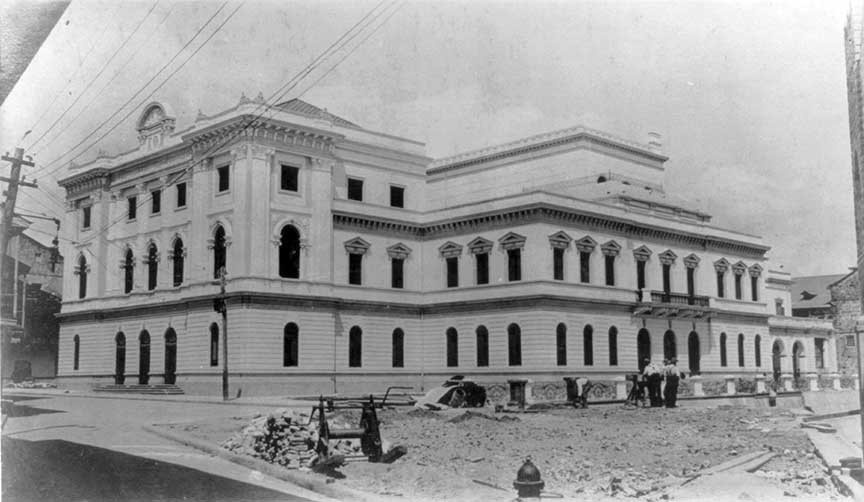

Paliaent House Panama

A revolution led by Philippe Jean Bunau-Varilla, an organizer of the Panama Canal Company, declared Panama independent from Columbia. U.S. naval forces prevented the Colombians from suppressing the revolt. On November 17th, the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty was signed between Panama and the U.S. giving the Americans exclusive rights over the Canal Zone.

The history of the Panama Canal is a testament to human ingenuity, geopolitical maneuvering, and the transformation of international trade routes. At the heart of this historical saga is Philippe Jean Bunau-Varilla, a French engineer who played a crucial role in the canal's creation and the political events surrounding it.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the strategic importance of a transoceanic canal was widely recognized. Maritime trade was heavily dependent on the lengthy and perilous journey around South America's Cape Horn. The idea of a canal through Central America, offering a shortcut between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, was therefore highly appealing. The French, led by Ferdinand de Lesseps, initially undertook this colossal task in Panama, but their efforts were ultimately thwarted by engineering challenges, devastating tropical diseases, and financial difficulties.

Bunau-Varilla, having been involved in the failed French project, remained deeply invested in the idea of the canal. Understanding the United States' growing geopolitical and economic interests in a transoceanic canal, he began to lobby key American figures, shifting their focus from Nicaragua to Panama as the ideal location for the canal.

During this period, Panama was a province of Colombia, and negotiations between the U.S. and Colombia over the rights to build a canal in Panama had reached an impasse. Sensing an opportunity, Bunau-Varilla supported and strategically orchestrated a revolution in Panama in November 1903. This revolution, backed by the presence of U.S. naval forces, successfully prevented Colombian troops from quelling the uprising, leading to Panama's declaration of independence.

Just days after this pivotal event, the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty was signed on November 18, 1903. Bunau-Varilla, acting as Panama's envoy, and U.S. Secretary of State John Hay represented the newly independent Panama and the United States, respectively. The treaty granted the U.S. extensive rights over the canal zone, including the authority to build, administer, and control a zone approximately ten miles wide across Panama. In return, the U.S. recognized Panama's independence and agreed to pay a significant sum upfront, followed by annual payments.

With the treaty in place, the United States commenced the monumental task of constructing the canal in 1904. The project, completed in 1914, overcame numerous challenges, including engineering hurdles and the combatting of diseases like malaria and yellow fever. The Panama Canal not only revolutionized global maritime trade by significantly reducing travel time between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans but also marked a significant moment in U.S. foreign policy and its relations with Latin America.

The canal's construction set a precedent for U.S. intervention in the region, a recurring theme throughout the 20th century. It also had profound implications for Panama's sovereignty and international trade patterns. The terms of the original Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty were later revised to address growing tensions between the U.S. and Panama. Ultimately, in a momentous event marking Panama's full sovereignty over its landmark, control of the Panama Canal was transferred from the United States to Panama in 1999.

In conclusion, the creation of the Panama Canal was not merely an engineering marvel but also a pivotal chapter in the geopolitical history of the early 20th century. It reflects the complexities of international relations, the ambition of visionaries like Philippe Bunau-Varilla, and the significant impact of human endeavors on global trade and politics.

>

>