Fries Rebellion

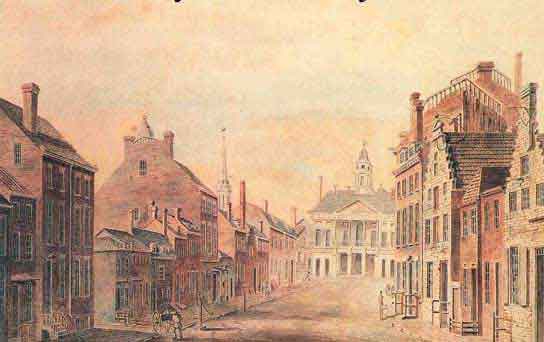

A View of Wall Street and City Hall in New York

In July 1798, the federal government approved a tax on property. John Fries of Pennsylvania led a group of Pennsylvanians in a revolt against this tax. Fries was captured, tried and sentenced to death for treason. President Adams pardoned Fries and his fellow rebels.

In July 1798, amid the backdrop of a burgeoning United States, the federal government, under the presidency of John Adams, approved a contentious tax on property. This tax, seen as a necessary measure by the government, was intended to raise funds for an anticipated war with France, known as the Quasi-War.

The imposition of this tax, however, was met with fierce resistance in some quarters, most notably in Pennsylvania. The leader of this dissent was John Fries, a man who would become synonymous with the rebellion that bore his name – the Fries Rebellion. Fries, an auctioneer by profession and a son of German immigrants, galvanized a group of Pennsylvanians, predominantly of German descent, who viewed the tax as not only burdensome but also as an infringement on their rights. This tax was particularly resented as it disproportionately affected landowners and was seen as an extension of federal overreach.

The rebellion was characterized by non-violent resistance, which included intimidating tax assessors and preventing the sale of property seized for tax delinquency. Fries and his followers believed they were standing up for their rights, drawing parallels with the American Revolution's rallying cry against taxation without representation.

The government's response to the rebellion was swift and stern. Fries and other leaders of the rebellion were captured and put on trial. In a landmark case, Fries was convicted of treason and sentenced to death, a sentence that sent shockwaves through the community and the young nation. This was a pivotal moment that tested the boundaries of the newly drafted Constitution and the government's approach to dissent and rebellion.

However, in a surprising turn of events, President John Adams intervened. In a move that was both humanitarian and politically astute, Adams issued pardons to Fries and his fellow rebels. This decision was not without controversy. It drew the ire of many in Adams' own Federalist Party who saw it as a sign of weakness and a dangerous precedent that could encourage future rebellions. For Adams, though, this was a decision grounded in a desire to maintain national unity and prevent the alienation of a significant segment of the population.

>

>