1818 Rush-Bagot Agreement

The Rush-Bagot Agreement between Great Britain and the United States demilitarized the Great Lakes and defined the border between the US and Canada at the 49th parallel. Negotiated by Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, the Rush-Bagot Agreement eliminated some of the most contentious issues between the United States and Great Britain.

The Rush-Bagot Agreement of 1817, initially a series of diplomatic exchanges between Richard Rush and Sir Charles Bagot, marked a significant milestone in U.S.-British relations post the War of 1812. Its ratification by the U.S. Senate on April 16, 1818, formalized the terms, reflecting a mutual commitment to demilitarization and peace.

This agreement was instrumental in demilitarizing the Great Lakes and Lake Champlain. Both the United States and Great Britain agreed to limit their naval armaments on these waters, setting a precedent for peaceful border management. Specifically, they agreed to have no more than one military vessel on Lake Champlain and the Great Lakes, with restrictions on the size and armament of these vessels. This laid the foundation for the world's longest undefended border.

Furthermore, the Rush-Bagot Agreement indirectly facilitated increased economic and commercial exchange between the United States and British North America (later Canada). By reducing military tensions and clarifying fishing rights, it paved the way for more cooperative relations in the region.

The resolution of the fishing disputes provided American fishermen renewed access to the rich fishing grounds around Newfoundland and Labrador. This was crucial for the U.S. fishing industry, which had been impacted by restrictions imposed during the war.

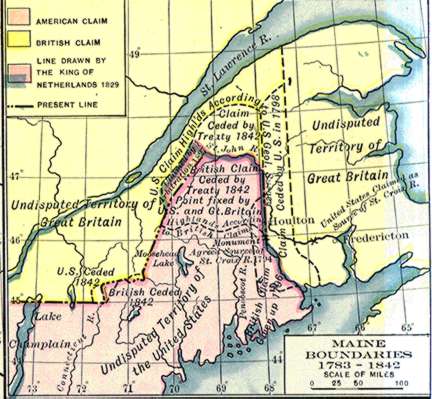

While the agreement set the 49th parallel as the border from the Great Lakes to the Rocky Mountains, it left unresolved issues, notably the Oregon Territory dispute. This would later be addressed in the Oregon Treaty of 1846, which also established the 49th parallel as the border in the west, extending to the Pacific Ocean.

>

>