1804 Alexander Hamilton Killed in Duel

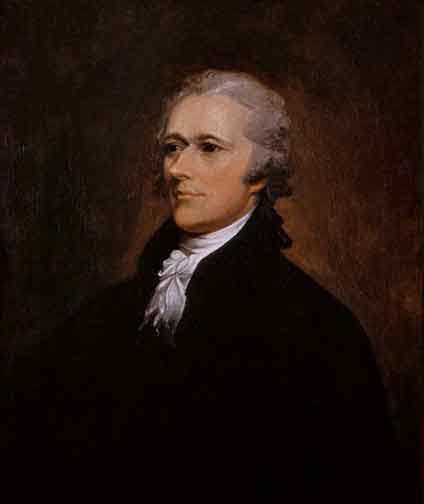

Alexander Hamilton

Aaron Burr challenged Alexander Hamilton to a duel. On the morning of July 11, 1804, Burr raised his gun, carefully aimed and shot Alexander Hamilton dead; thus ending the life of one of America's founding fathers.

The election of Thomas Jefferson in 1800 and the subsequent admission of new states into the Union marked a significant decline in the influence of both the Federalist Party and its prominent leader, Alexander Hamilton. This political shift came in an era characterized by intense partisan rivalry and the shaping of early American political ideologies. Some radical Federalists, alarmed by their waning influence and the growing Democratic-Republican sway under Jefferson, proposed the drastic measure of forming a new union of New England States. They approached Alexander Hamilton with this idea, but he staunchly refused to entertain such a radical notion, remaining a firm believer in the constitutional union.

Rejected by Hamilton, these Federalist radicals turned to Aaron Burr, who was then serving as Vice President under Jefferson. Burr, a complex figure with his own political ambitions, was also contesting the governorship of New York. The radical Federalists saw in Burr a potential ally and offered their support in his gubernatorial campaign, hoping he would back their separatist aspirations in return. Despite this alliance, Burr suffered a defeat in the New York gubernatorial election of 1804. He attributed this loss largely to Alexander Hamilton's influential opposition. Hamilton had been a key figure in the 1800 presidential election deadlock, where he had favored Jefferson over Burr for the presidency, despite their differing party affiliations. This preference was rooted in Hamilton's distrust of Burr's character and political intentions.

The 1800 election had indeed been a turning point. After an intense and deadlocked electoral process, which lasted through 35 ballots in the House of Representatives, Hamilton's support helped tilt the balance in Jefferson's favor. Deeply aggrieved and feeling his honor besmirched by Hamilton's persistent antagonism, Burr challenged Hamilton to a duel, a common though controversial practice for settling personal disputes among gentlemen of that era.

Hamilton, despite his personal opposition to dueling—a stance tragically underscored by the death of his eldest son, Philip, in a duel in 1801—felt compelled to accept Burr's challenge to avoid the stigma of cowardice. Dueling, while illegal in many states, including New York and New Jersey, was still a prevalent part of political and social life among certain classes.

On the fateful morning of July 11, 1804, Hamilton left his home in New York City in the early hours, keeping the duel a secret from his family. He crossed the Hudson River to Weehawken, New Jersey, a popular dueling ground hidden beneath the cliffs of the Palisades. The duelists agreed upon a distance of ten paces. In a moment marked by tension and historical consequence, Burr took aim and fired, striking Hamilton. The wound Hamilton sustained proved fatal; he died the next day, leaving a legacy as a Founding Father and a principal architect of the American financial system. His death also marked a significant turning point in the public perception of dueling and contributed to its decline in American society.

>

>