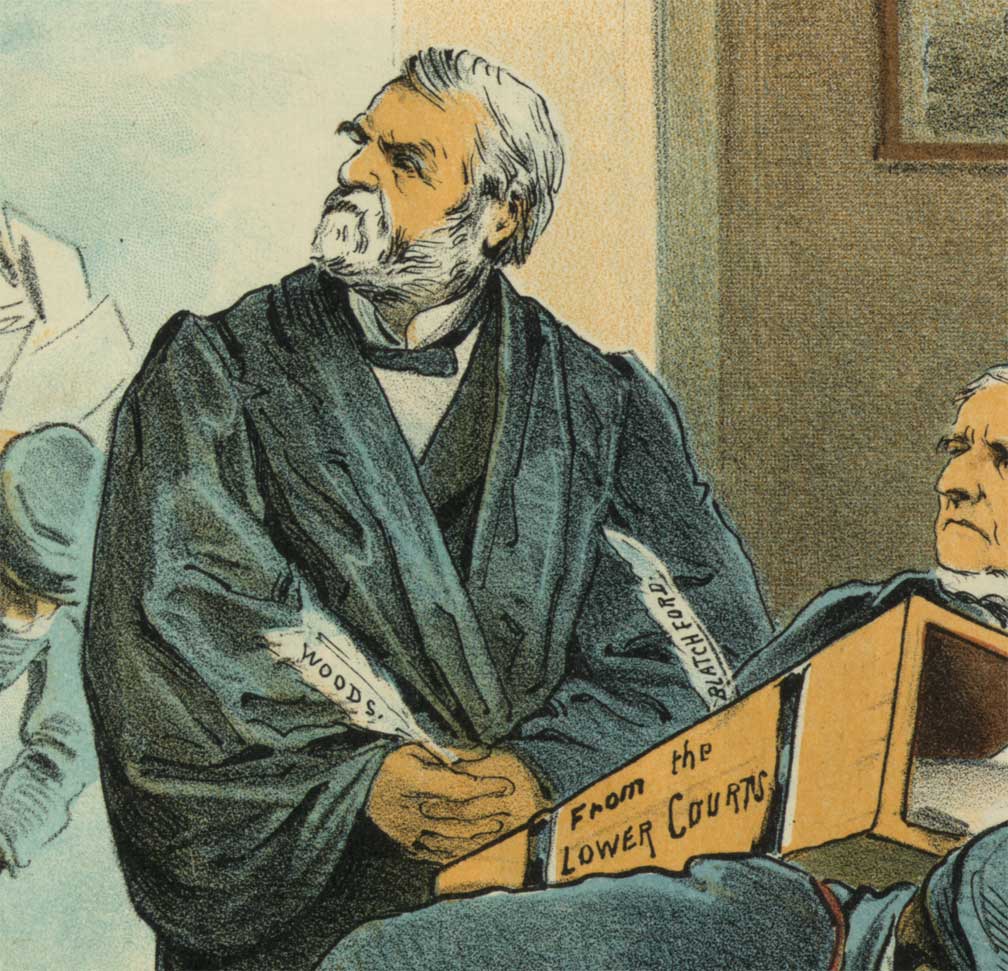

William Woods

William Burnham Woods was born in Newark, Ohio, on August 3, 1824. He attended Western Reserve College for three years, and graduated as valedictorian from Yale College in 1845. Woods returned to Newark to study law with a local attorney, S. D. King. After he was admitted to the bar in Ohio in 1847, he joined King’s law firm as a partner. In 1855, he married Anne E. Warner, with whom he later had two children.

Woods began as a Whig, but soon became a Democrat, and was elected mayor of Newark in 1856. The next year, he joined the state legislature, serving as Speaker in his second term. When the Democrats became the minority party in 1859, Woods became the minority leader, opposing President Lincoln and his Republican party. With the outbreak of the Civil War, however, he gave his support to the President and the cause of the Union. In 1862, Woods joined the Union army, as a lieutenant colonel of the Seventy-sixth Ohio Regiment. He took part in the Battles of Shiloh and Vicksburg, and joined General William Sherman in his march through Georgia. At the end of the war, Woods, who had attained the rank of brigadier general, rode through Washington, D.C. in the Grand Review of the Union Troops. Generals Sherman, Ulysses S. Grant and John A. Logan all supported Woods’ promotion to brevetted major general. After the war, Woods was assigned to Mobile, Alabama, and chose to remain in Alabama after he was released from the army in February 1866.

Woods worked as a lawyer, became a cotton planter and invested in iron works. By now a Republican, he was elected as a chancellor to Alabama’s southern chancery court. When Congress created nine circuit judgeships in 1868, Woods was appointed to the Fifth Circuit (Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana and Texas). He worked in this capacity for eleven years, and also served as reporter for the federal courts’ decisions. Although he was a northerner who had served in the Union army, Woods was able to gain the respect of southern judges and attorneys, as well as the residents of the communities over which he presided. He strove to make the federal courts fair and approachable to southerners.

Woods was considered for a nomination to the US Supreme Court in 1877, but was passed over in favor of John Marshall Harlan. Three years later, however, President Rutherford B. Hayes nominated Woods to replace the resigning Justice William Strong. Woods was confirmed on December 21, 1880, making him the first justice to have been appointed from a state that had been part of the Confederacy since 1853.

Once on the Court, Woods was overwhelmed by the phenomenal caseload given to the justices. It was not until 1891 that the overwhelming caseload was significantly relieved by the creation of the Circuit Court of Appeals. During his six and a half years on the Court, Woods wrote 159 opinions, more than any other associate justice. Few of those cases dealt with constitutional issues, and only in eight cases did he dissent from the majority.

In the spring of 1886, Woods became ill and, after an extended visit to California for the purposes of speeding recovery, he died in Washington, D.C., on May 14, 1887.

>

>