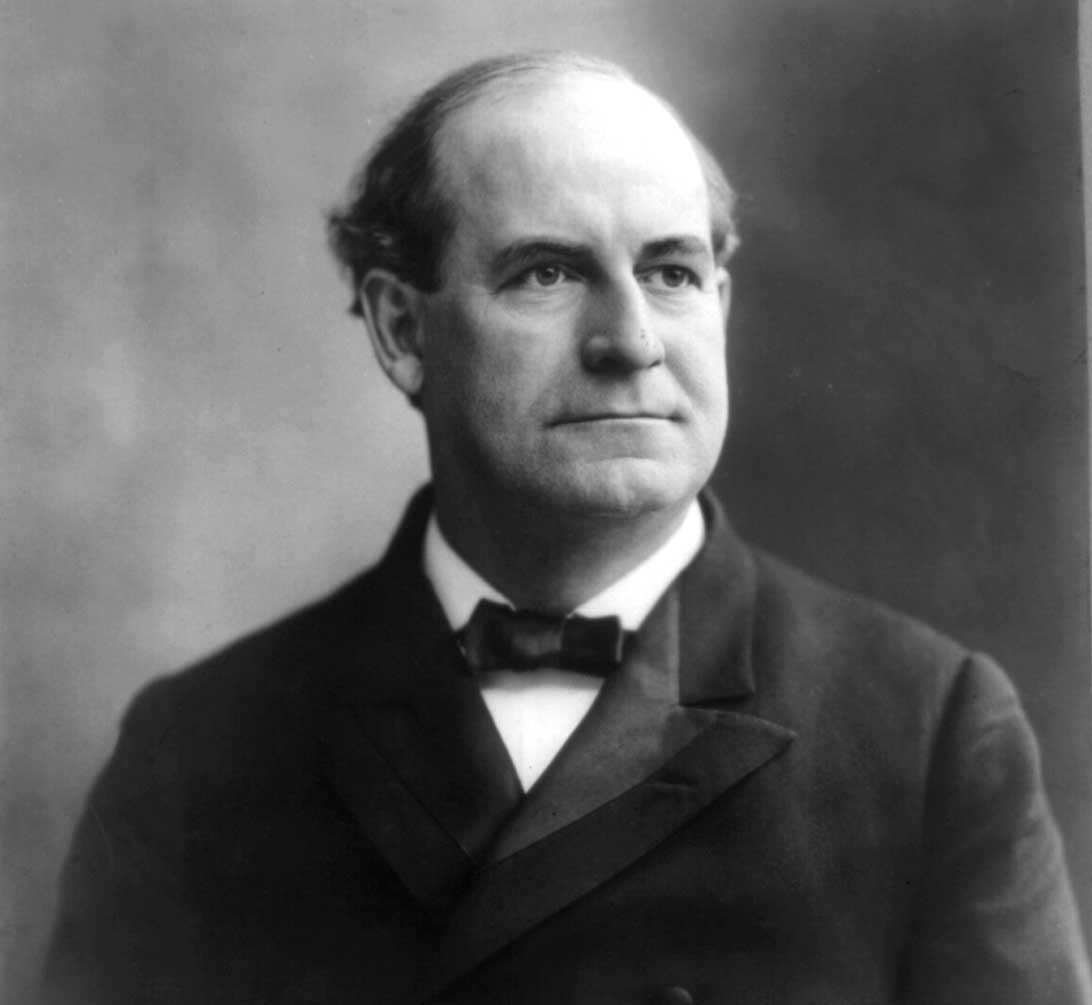

William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan was born on March 19, 1860, in Salem, Illinois. He graduated from Illinois College in 1881, and Union College of Law, Chicago, in 1883. Bryan practiced law in Jacksonville, Illinois until 1887, when he moved to Lincoln, Nebraska. In Nebraska, he was elected to the US House of Representatives as a Democrat in 1890. He joined the free silver advocates, and voted against the repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act in 1893. After being defeated in the 1894 senatorial election, he became editor-in-chief of the Omaha World-Herald, a pro-silver newspaper. At the 1896 Democratic convention in Chicago, Bryan gave a speech in favor of free silver, in which he exclaimed "we will answer their demand for a gold standard by saying to them, ‘You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns, you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold." This "cross of gold" speech launched Bryan into the national limelight, and won him both the Democratic and Populist nomination for President. Bryan lost the election to the Republican candidate, William McKinley.

During the Spanish-American War, Bryan served as a colonel. After the war, in 1900, he was nominated for President by the Democrats in 1900. Defeated again by McKinley, he founded the Commoner in 1901, through which he expressed his pro-silver, anti-imperialist views. After another unsuccessful bid for President in 1908, losing to William Howard Taft, Bryan supported Woodrow Wilson as the Democratic nominee in 1912. When Wilson was elected, he appointed Bryan Secretary of State.

As Secretary of State, Bryan worked on a number of international arbitration treaties and, despite his anti-imperialist beliefs, supported the preservation of American interests in South and Central America to the exclusion of European influences. With the beginning of World War I, Bryan supported strict neutrality, and opposed American loans to the Allies. He resigned from his Cabinet post in 1915, protesting what he held to be Wilson’s overly belligerent policies toward Germany after the sinking of the Lusitania. Nevertheless, he supported Wilson’s 1916 renomination for President. After leaving public service, Bryan’s eloquence and energy made him a popular lecturer.

Bryan was a study in apparent contradictions. He sought to expand the democratic process but distrusted experts in the civil service and academia. He defended the industrial worker, but tried to subordinate his interests to those of rural Americans. He fought against privilege and inequality, but failed to defend the rights of African Americans and was even associated with the Ku Klux Klan. He insisted on independence for the Philippines and neutrality in World War I, but took part in interventionist and imperialist policies toward Mexico and the Caribbean. In his own idiosyncratic way, he sought to defend the roles of Christianity, majority rule, the rural way of life and the American mission in American society and politics. A religious fundamentalist and staunch opponent of the theory of evolution, he was one of the prosecutors in the celebrated Scopes Trial of 1925 in Dayton, Tennessee. During the trial, defense attorney Clarence Darrow cross-examined Bryan intensely, tearing him to pieces and revealing the prosecutor’s lack of knowledge of modern science. While the prosecution won the trial, national commentators and the work of the defense served to discredit the fundamentalist cause. Bryan died in Dayton only a few days after the trial, on July 26, 1925.

>

>