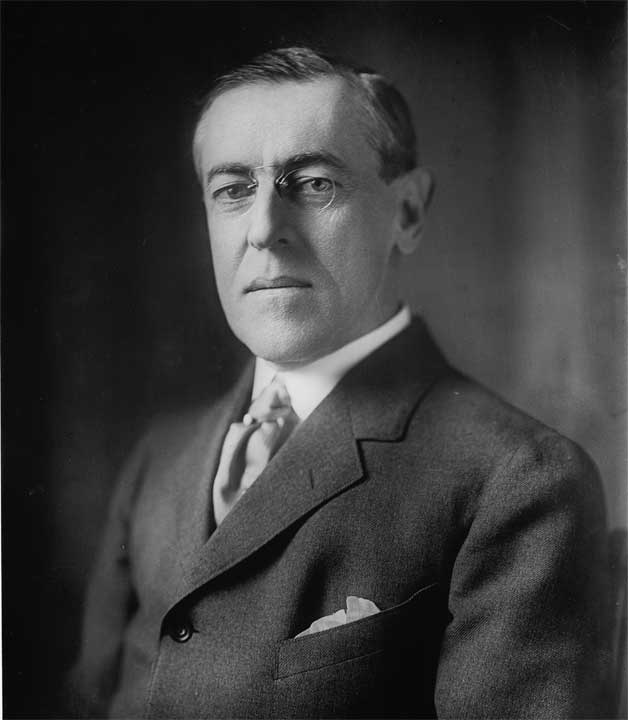

Woodrow Wilson

1856- 1924

American Politician

President Woodrow Wilson was born in Staunton, Virginia. In 1875, he enrolled in Princeton College. After completing his studies, Wilson entered the University of Virginia Law School, but he was forced to resign for health reasons.

He taught himself law and was admitted to the bar in 1882. He tired of the law and decided to enroll at John Hopkins for a PhD in political science, which he earned in 1886.

From 1890 to 1902, Wilson was a professor of jurisprudence and political economy at Princeton. During this time he published a series of books, including a five-volume history of the American people. From 1902 to 1910, Wilson was President of Princeton, where he reorganized the methods of teaching.

In 1910, Wilson was elected Governor of New Jersey. As Governor, Wilson declared war on the local political monopoly. He enacted laws to insure direct party primaries and require candidates to file campaign financial statements.

Wilson was elected President in 1912, coming to power on an activist domestic affairs agenda based on his belief in a strong role for the office of the Presidency. He considered himself the direct representative of the American people, and was determined to enact legislation that he felt met their needs. He called his program "the new freedoms," which included expanded anti-trust legislation, child labor laws, workers' compensation for federal employees and an eight-hour day for railroad workers.

Wilson also helped to establish the Federal Reserve System, the first national banking system in the US since the time of President Jackson.

Wilson followed a liberal foreign policy. He ended the policy of Dollar Diplomacy, in which the United States could use force to enforce economic policies. He did not, however, object to the use of force for the sake of democracy.

He refused to recognize the Mexican dictator Huerrita. The United States came to the brink of war with Mexico after one of Huerrita's generals ordered American sailors seized. Wilson then ordered the American armed forces to seize the Mexican port of Vera Cruz. When the Mexican bandit Pancho Villa attacked Americans along the Mexican border, Wilson ordered American troops to pursue him deep into Mexico.

With the outbreak of World War I, Wilson's policies were sorely tested. He opposed American involvement in what he felt was a European war, though his personal sympathies lay with the British and French. German submarine attacks against shipping vessels strained Wilson's determination to remain neutral, especially in the case of the sinking of the Lusitania.

In 1917, the combination of German submarine warfare and the discovery of the Zimmerman telegram, in which the Germans promised Texas and California to the Mexicans, finally forced Wilson to ask Congress to declare war against Germany.

Wilson was a strong war President. He successfully rallied the American people in support of the war effort. He was particularly successful in portraying the war as a fight for democracy. He promoted a policy that he called his "Fourteen Points." He was ultimately disappointed that the peace treaties culminating in the Treaty of Versailles bore little resemblance to his Fourteen Points. Perhaps Wilson's greatest disappointment was the Senate's rejection of United States participation in the League of Nations.

Wilson suffered an incapacitating stroke in September of 1919. His ability to function as President was greatly reduced for the remainder of his administration.

>

>