1917 Race Riots in Illinois

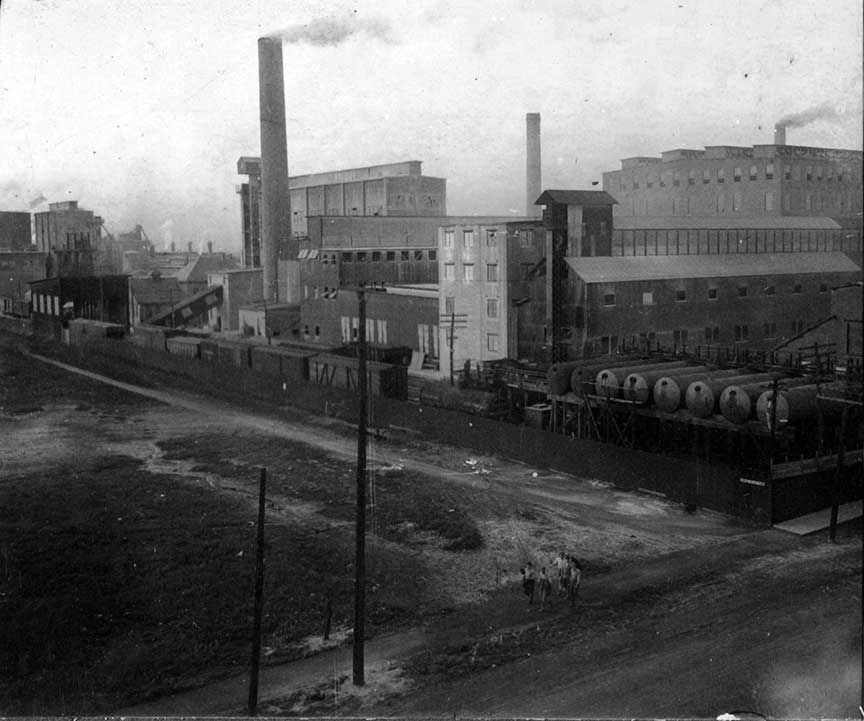

Aluminum Ore Company

A serious race riot broke out in east St. Louis, Illinois. Forty Blacks were killed and martial law was declared. The riots broke out after Blacks were hired in a factory with government contracts.

The roots of the East St. Louis race riot can be traced to the broader context of the Great Migration, during which hundreds of thousands of African Americans moved from the rural South to the industrial North in search of better economic opportunities and escape from the oppressive conditions of the Jim Crow South. East St. Louis, with its burgeoning industrial sector, became a destination for many Black migrants. The city’s factories, including those with government contracts related to the war effort, offered employment opportunities that were scarce in the South.

However, the influx of Black workers into East St. Louis created tensions with the established white working-class population. White workers feared that the new Black arrivals would undercut their wages and take their jobs. These economic anxieties were exacerbated by existing racial prejudices, creating a volatile atmosphere. Employers sometimes exploited these tensions by hiring Black workers as strikebreakers, further inflaming white workers’ resentment.

The immediate spark for the riot came in May 1917, when a labor dispute at the Aluminum Ore Company led to the hiring of Black workers to replace striking white workers. This move was perceived as a direct threat to the livelihood of white workers, and tensions quickly escalated. On May 28, a meeting of white workers at the City Hall turned violent as rumors spread that a Black man had killed a white man. A white mob rampaged through downtown East St. Louis, attacking Black residents and burning homes and businesses.

The violence temporarily subsided, but the underlying tensions remained unresolved. On July 1, 1917, the situation exploded again. After reports of a Black man firing at a white man, white mobs began attacking Black neighborhoods in East St. Louis. The violence quickly spiraled out of control. Over the next two days, white mobs, including many armed men, roamed the streets, attacking Black residents and destroying property. Entire neighborhoods were set ablaze, and Black families were forced to flee for their lives.

The local police force was unable, and in some cases unwilling, to control the violence. Reports emerged of police officers participating in the attacks or standing by as the mobs raged. Illinois Governor Frank Lowden eventually called in the National Guard, but by the time they arrived, the damage had been done. Martial law was declared, and the National Guard began to restore order, but not before at least forty Black individuals had been killed, hundreds had been injured, and thousands had been left homeless.

The East St. Louis race riot drew national attention and condemnation. The brutality of the attacks and the apparent complicity of local authorities shocked many Americans. The NAACP, which had been formed just a few years earlier, organized a Silent Parade in New York City to protest the violence and the broader injustices faced by African Americans. On July 28, 1917, nearly 10,000 Black men, women, and children marched down Fifth Avenue in silence, carrying signs that read, “Your Hands Are Full of Blood” and “Pray for the Lady Macbeths of East St. Louis.”

Despite the outrage and calls for justice, few of the perpetrators of the violence were ever held accountable. A congressional investigation was conducted, but it led to no significant actions to address the underlying causes of the riot or to provide justice for the victims. The East St. Louis race riot remains a stark reminder of the deep-seated racial tensions and economic inequalities that have plagued the United States.

>

>