WAshington Burns

On August 18, 1814, British forces marched on Washington. After a brief battle on the road known as the Battle of Bladensburg, the British forces defeated the Americans who withdraw in disarray, thus opening the road to Washington. The British burned the White House and the Capitol, but a strong rainstorm saved the rest of Washington. The British, under orders not to hold any territory, withdrew.

On August 18, a substantial British force under the command of Major General Robert Ross arrived at the confluence of the Pawtuxet River. This strategic position enabled the British to advance towards Washington. The American military, in its nascent state, faced a severe shortage of troops, with only 250 regulars available to resist the impending threat. Despite this, the British marched north without encountering significant resistance from the Americans.

On August 24, at the town of Blandsberg, the Americans made a valiant stand. However, the British swiftly overwhelmed the initial defensive line at the bridge. Subsequently, they swiftly conquered the second defensive line, and finally, the order was given to retreat from the third defensive line. The British suffered at least 64 casualties, while the Americans lost 24. Consequently, there was now no obstacle between the British and Washington.

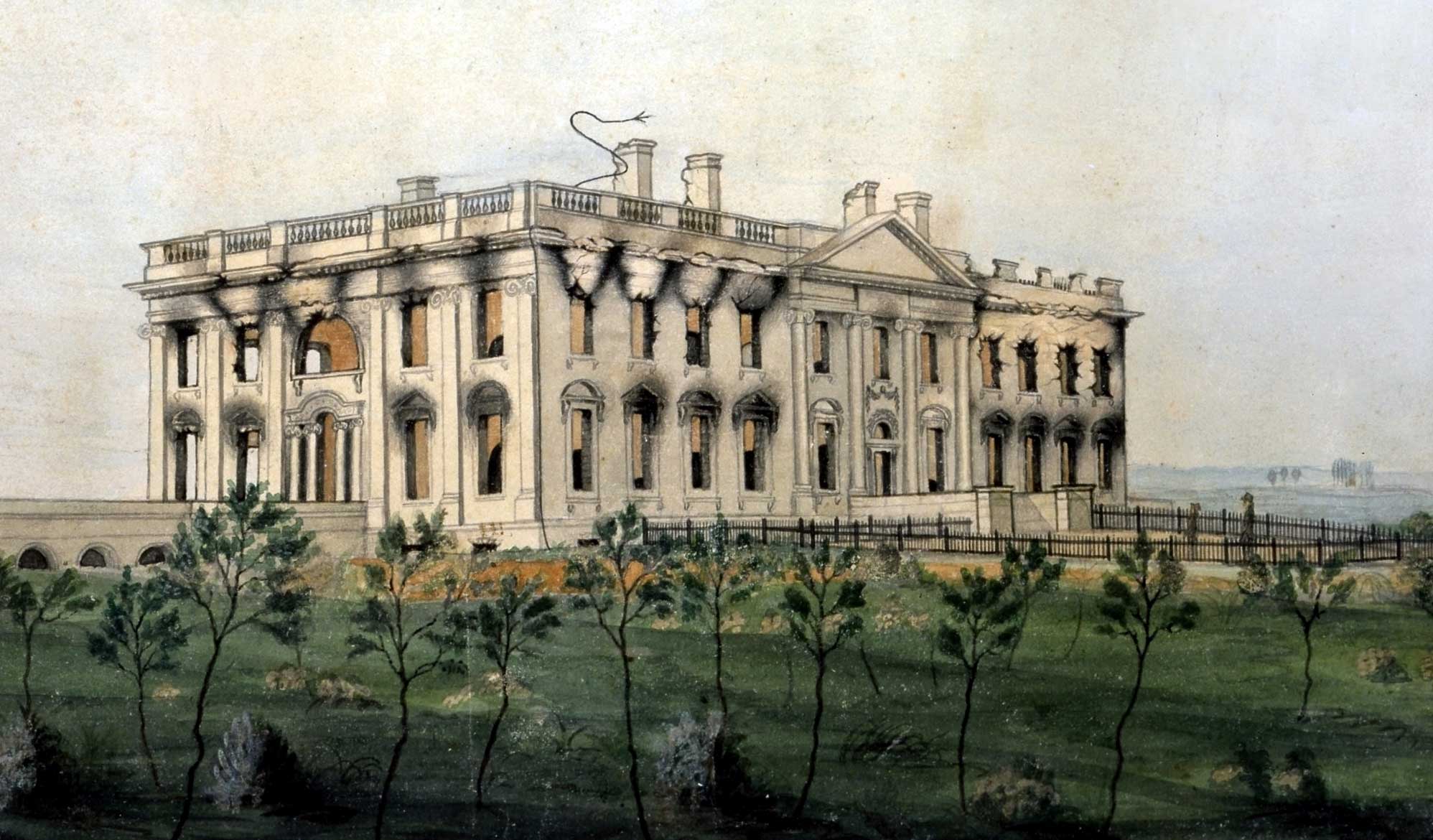

Meanwhile, in Washington, Dolly Madison made a remarkable historical feat by safeguarding key documents from the White House and the renowned portrait of George Washington, thereby ensuring their safety. Upon their arrival in Washington, the British embarked on a destructive rampage, burning down the major government buildings, including the President’s House (now known as the White House), the Capitol Building, the Treasury, the State Department, and the War Department.

Despite their presence in Washington for only one night, the British’s primary objective was not to occupy the city but rather to conduct a raid.

>

>